The Intel compute element is Intel’s new modular PC form factor to extend benefits of expandability to their largely popular line of Intel NUCs. However, the product is as dead as it is even not out of the water. Is the Intel compute element doomed to fail? Let’s take a close look at Intel offerings.

What is the Compute element?

I am a big fan of Intel NUC series. When Intel premiered their new Computer element at CES 2020 last January, it got me really excited for what to come. Intel touts that their new line of Next unit computing line (NUC for short) elements are an entirely new way to design and build solutions and Mini PCs. With aims to deliver flexibility of modular computing.

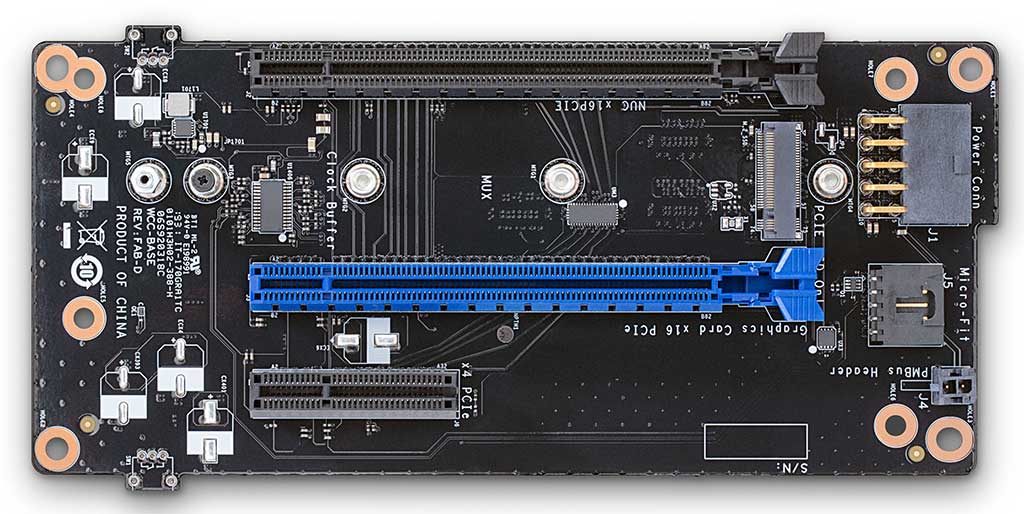

Also, Intel’s idea of a modular card PC is an interesting one. Having said that, having a closer look at the compute element card, it is essentially a large PCI-E express card slot with a cooling fan shroud built on it. You won’t be faulted if you think it is a graphic card at first glance.

Some assembly required

The graphic-card looking thing is actually the entire computer itself, CPU and Input/output ports. So what Intel had done here is to pack an entire NUC unit into the card. They essentially pulled out the Innards of their NUC series into a PCI-E bus powered card. Hence you get the familiar bells and whistles of 2 so-DIMM slots a well a M.2 slots for storage, on the card itself.

The catch is that you can’t just turn it on and run it yet. This modular accessory will then go into a (propriety) chassis which has two PCI-E bus interfaces, one for this Compute element and the other for an external PCI-E 16x full graphics card.

Having said that, what you get is a NUC-like bare-bone system. Hence, you have to purchase the compute element case, RAM, M.2 storage, and even a GPU itself to complete the package.

Bringing dedicated GPU to the NUC line

How I see Intel would like to position this product is to sit above their NUC. You may remember NUCs as the tiny 4 inch by 4 inch super compact mini desktop with pretty beefy ultra-book level “U” model CPUs soldered on them. However, the Achilles heel on those NUC are pretty horrible graphic performance. They often come equipped with on board Intel HD integrated non-discreet graphics options. Also, it featured an Intel Iris Pro graphics which is really at best, not much different in performance despite the marketing.

Furthermore, moving up the NUC chain is Intel’s focused Hades Canyon NUCS “G” series. These larger than NUC systems features Intel CPUs with AMD Vega graphics (and remarkably one of the few blue-and red moments). They are targeted mainly at gamers and professional workstation users (though more to gamers).

Additionally, this particularly those dealing with computer gaming or aided graphic design, simulations or video editing workloads, which still essentially Ultrabook processors, such as those similar found on the Dell XPS 13 range. Giving credit to Intel, these Ultrabook CPUs had proven to be rather capable machines for such professional workloads while still being able to sip minimal power.

Solving the graphics challenge

But still, the top of the line NUCs with Vega GPUs are still nowhere near the performance of a dedicated GPU. Till today, the only way to beef up your mini-NUC graphic capability is to add on an external GPU. This comprised of a separate enclosure which links your CPU to an external PCI-E. Though this solution is a far cry from the first generation e-GPUs we see on the ASUS and Alienware’s propriety graphics amplifier e-GPU cases.

Moreover, even at best, our present day thunderbolt 3 e-GPUs interface loses up to 20-30% of your GPU’s maximum performance. This is due to parasitic losses within I/O buses as opposed to a directly bus-connected PCE-E 16x slot to your CPU in desktop setups for instance. This inherits bandwidth loss is due to Southbridge bottlenecks with several middleman interfaces sitting between your CPU and external GPUs (e-GPUS). This was as far as we become in extending desktop-level graphic performance for integrated graphics systems.

Compute element 3rd party partner offerings

To date, third party manufacturers such as Razer and Coolermaster has announced their own line of Intel compute element cases to support the idea. Sticking to the reference layout which Intel pioneered with their first release compute elements cases. Razer being Razer of course souped-up their NUC offerings with their larger “Tomahawk” chassis to take full length graphics card, like a Titan V or RTX 2080Ti, with a sizable bundled PSU to boot.

However, just as with every first release, do expect to pay a premium being a first adopter. Coolermaster has similar offerings with their more affordable sub $200 USD NC100. Having said that, the computer element case aims to throw this whole concept over its head with their mini-ITX sized cases which are such. The case come equipped with at least a 500W PSU able to take up power hungry CPUs and GPUs.

Still I am surprised that Intel choose to sell the card and case separately knowing that you actually need both for the system to actually run. It could probably due not to cannibalise the case offerings by third parties as well as providing additional market options to the consumer.

Craving out a niche market space

The question now is the purpose of the Computer Element line. Also, is Intel shooting themselves in their foot by forgoing the biggest unique selling point of the NUC series? Namely its iconic compact footprint and energy efficiency. The compute element is also not that small as with the tiny NUCs we come to love. It sits as big as a typical Micro-ITX form factor PC case.

Moreover, the benefits are only evident you are within the NUC ecosystem, if you open up the hostility of alternatives the offerings are tad not as attractive. Also, processor ranges had been greatly increased across the board, now you have the ability to spec out your card with consumer i7s up to professional Xeon low-powered M CPUs with remarkably, ECC memory support. Do note that these are not the high powered server CPUs despite being called “Xeons” (Similarly to Dolby Atmos at home not equals to that in the cinema).

Not quite future-proof

I won’t see the computer element directly competing with the current range of Intel NUC. While the consumer could welcome the new variety of NUC products to meet you computing needs. The continued success of the element also depends largely on the adoption rate, which at this point of writing is still lacklustre. You won’t want to find yourself stuck in a situation shelling out at least $2000 on proprietary hardware with promises of upgradability only to find the product line discontinued the year after.

Also considering that most DIY PC parts had been modular for decades, the compute element is not a novel. What the compute element does is that it brings the flexibility to upgrade the innards bring. It does reduces the learning curve and the makes it less daunting for less technically inclined customers to upgrade their computer.

It is Expensive

One of the biggest drawbacks of the Compute element is its price. Obtaining the card itself is not just it. In addition to the rather expensive compute element card itself, you need to purchase an additional enclosure to house your card just to even get started. Additionally, you have to purchase on top of the compute element case, RAM, Storage, and even a GPU itself. This means even as a bare-bone system. The cost does add up.

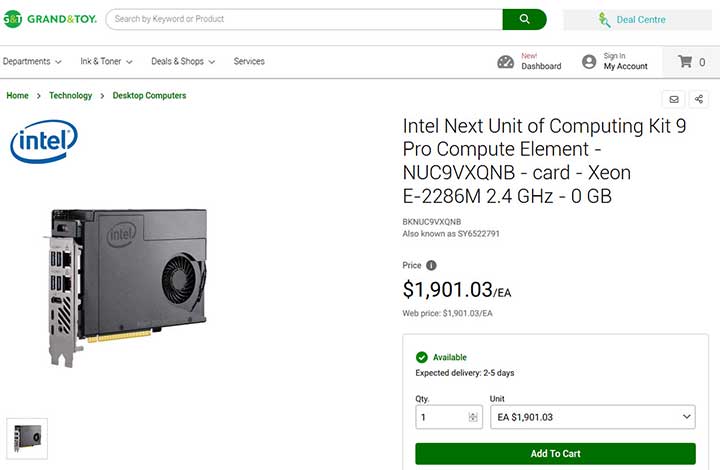

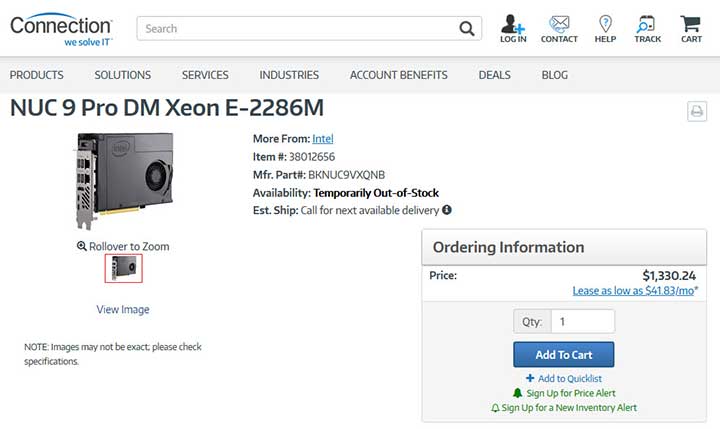

To date, even Intel had not, or is unwilling to publish recommended pricing of their Intel Compute card. A dig and poke around online retailers currently retailing the card yielding sale prices of $1,050 USD for a Core i5 variant and about $1,330 USD ($1,895.28 SGD) for the Xeon E-2286M card.

Also, referencing Intel’s recommended price of $623.00 USD ($880.45) just for the Xeon CPU, we can see the board on average add at least a $1000 USD premium over the cost of the processor. Bump up your specs to the higher end Xeon CPUs and you can see prices nearing $3000 SGD just for the board itself.

The entire Element lineup

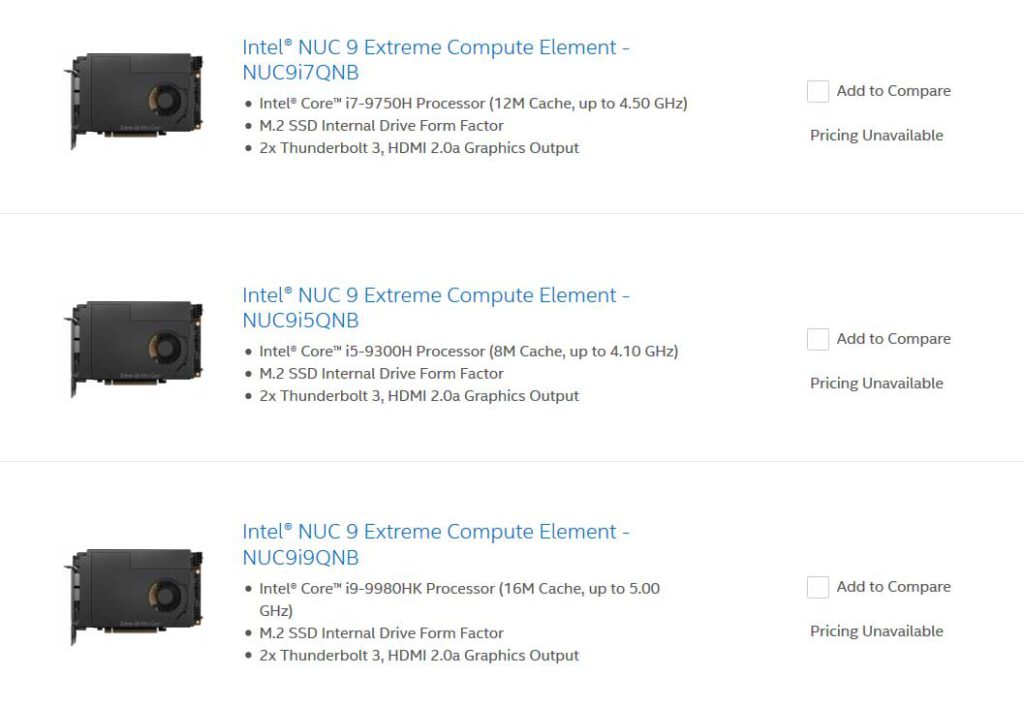

A further look at intel’s product listing on their website features 7 products in the line-up, starting from their NUC 9 Extreme Compute Element Core i5-9300H Processor to their Pro line Xeons. The entry Core i5(NUC9i5QNB) has 8MB Cache and able to turbo up to 4.10 GHz.

Next up are two i7 CPUs, namely the 9750H (NUC9i7QNB) and 6-core 9850H (NUC9V7QNB), with a corresponding 12MB Cache, up to 4.60 GHz. Notably, this CPU has a passmark score in the range of about 11547, with a recommended starting price of $395.00 USD on Intel ARK’s official recommended pricing just for the CPU (the actual card will cost more).

Next up, their Core i9-9980HK Processor CPU features 8 cores and a passmark score of about 16065 (NUC9i9QNB with 16MB Cache, up to 5.00 GHz boost clocks). The top of the line NUC compute element is their range topping NUC9VXQNB with a Xeon E-2286M Processor, it has similar performance to the 9980HK but with EEC memory support.

While the idea of modular PC parts is not novel. It is an expensive solution to upgrade your CPU, which involves changing out the entire motherboard assembly with all its IO ports, which are all soldered on together with the CPU. All cards spots similar I/O with M.2 SSD Internal Drive Form Factor 2x Thunderbolt 3, HDMI 2.0a Graphics Output, as well as a 3 year limited warranty.

Comparison to market offerings

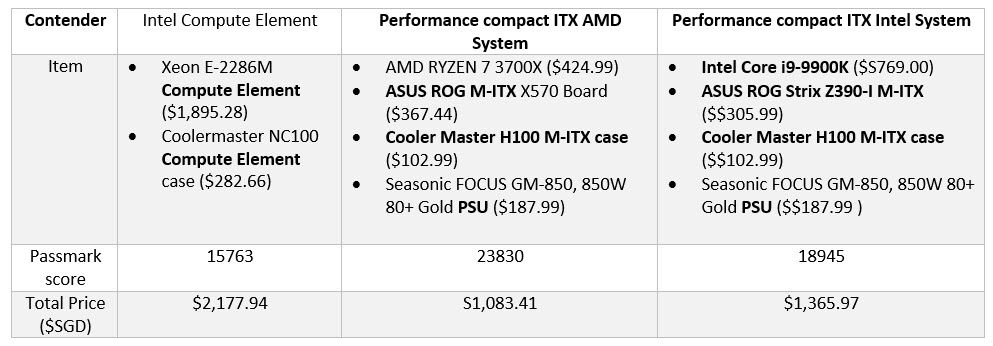

Let’s compare market alternatives. Putting their top performing Xeon E-2286M Compute Element against an equivalent similar M-ITX barebone form factor system price for both an AMD and equivalent Intel system. The price to performance difference are shocking.

Giving the best possible case for the Compute Element, I factored in the cost of the cheapest compute case (the reasonably priced coolermaster NC100), we can see the barebone system costing at least $2,177.94. Again, do note this excludes RAM, storage and the GPU cost itself.

I had spec-ed both the AMD and Intel systems to take on similar M-ITX casing and performance motherboards to provide a fair alternative to the NC100 M-ITX sized compute element case. Also, do note that I had removed the cost of common items, such as Graphics card, storage and RAM. So-DIMM and regularly-sized DIMMs costs about the same here now. The Ryzen 7 system costs a whopping 2 times cheaper than the compute element solution, while the Intel i9 system costs half the price.

Furthermore, the Ryzen 7 3700x I had chosen is not even the top end of the series. It already had the Xeon E-2286M Compute Element already beaten by a passmark score margin of 30%, by a Ryzen CPU which was released 10 months ago on July 2019! In comparison Intel’s very own i9-9900K has a 17% performance gain over the Xeon E-2286M and the next up i9-9980HK.

The unique selling point?

So we see, across the board, the only benefit for the Compute element is rather evident. So is Intel is trying to position themselves with the Compute Element selling performance? Footprint? Definitely not on costs?

With a $1,766.62 SGD starting price for the Core-i5 Compute Element and case can get you a more capable and better-performing Ryzen 7 system with at least $600 change to spare. Go for the top end Xeon E-2286M Compute element at $2,177.94, add in an mid-range RTX 2060, 16GB of RAM and at least a 256GB SSD into the mix, and expect your compute element solution to cost within the sub $3500 range. Not exactly affordable at all.

On power maybe? As both the Xeon E-2286M and 9980HK are rated at 45W, though the Ryzen 7’s 65W peak power. However do note that both Intel and AMD measure TDP differently, with Intel typically offering nominal values while AMD publishing peak values. That is not an apple-to-apple comparison and a whole another story of its own.

The lowdown

All in all, like the not-so successful Intel compute stick/card, which didn’t quite caught on due to lack-luster performance to price. Credit to intel, you can genuinely see this as Intel’s solution to solve lacklustre GPU performance problems always plaguing the NUC series. On a capability stand front, it is great and exciting milestone for any NUC owners out there. Unless Intel is able to drastically reduce the price of the entire Compute element range, it offers one of the worst performance-for-buck solutions out there, which I do not recommend putting your money on.

Only if you are within the NUC ecosystem, and unless you are a die-hard Intel mini-PC diehard fan, then I would say go for it, as it is possibly Intel most powerful and stylish NUC solution to date.

For others, including myself, I find it is a hard sell to recommend the Intel Compute Element, given close market alternatives with more performance bang for the buck.

[…] Still, there is plenty to be exited about Intel’s new Rocket Lake. However, I do hope that Intel is not living life in their own bubble and dragging their feet along given the new Ryzen 5000 already pulverizing them on the CPU battlefield. I do hope it does not suffer the same bad fate as intel’s NUC compute. […]

[…] They stuck to what is tried and tested. This is also considering their similarly dissapointing compute units were not well-received either. Performance-wise, the lack of 6 core CPUs is disappointing though, […]

[…] this translate to better system performance. Last year the 9th-gen NUC extreme “Ghost/Quartz Canyons” topped out with the 8-core Xeon 2286M, it is nearly identical in […]