Getting there

Perched on a small hill by the Bukit Timah hill view area is the site of the Old Ford factory. The old former factory used to be an actual busy manufacturing plant, well served by the adjacent railway for resources and shipment of cars, part of the early “industrial” years of early Singapore manufacturing. Built in 1941 by the Ford motor company, the factory was as the company’s first assembly plant in Southeast Asia conceived to feed to growing boom of cars in Singapore and the region. Now, it is converted to a museum, you can find the old factory grounds along upper Bukit Timah road, just off Bukit Batok park near the Bukit Timah rail mall. It is well served by public buses, which you can easily connect from the nearest MRT stations (Beauty world or Hillview MRT station). If you are driving, parking is free in the museum grounds, with space for about 20 cars.

From the attraction front sliding gate, a short climb up the hill brings you to the museum entrance. Presently, the only the façade of the factory warehouse remains, with most of the compound now taken up by high end residential condominiums around the Bukit Timah neighborhood. The compound is home to the National Archives of Singapore, who manages the entire land plot, gazette as a protected place given historical significance.

The Ford motor factory

As history has it, the factory building wasn’t used as what it was intended for during the Second World War when the Japanese took over Singapore. The factory was built and completed just months before the first Japanese invasion of Singapore, where it was repurposed as a war factory by Nissan to fuel the Japanese war effort in the region. It was not until after the war where it was reverted back into car factory again before its eventual closure.

The museum lobby is bare and simple, laid with a concrete floor with a reception counter surrounded by industrial-looking supports which were part of the factory’s original support beams. The entrance is in contrast to a rather funky looking visitor toilet, which the museum staff claims is very “Instagramable”. A couple of automotive posters depicting the Ford motor revolution and car models are the only hints of the building’s automotive origins. The galleries are split into two sections, one focused before the Japanese occupation, where the bulk of the museum is focused on and the second on the life involved in rebuilding Singapore. A lighted table seats in the lobby by the entrance of the Wartime gallery. A TV screen showcasing videos of early life in Singapore before the world war plays by the sliding door entrance to the galleries itself, showing you the peaceful lifestyles of the people before the war hits.

Pre-war gallery

The museum galleries make up of 4 main sections, each focused on different timelines of the war told through separately themed rooms demarcating the stages of war and follows a linear route back out to the lobby. The first two zoned sections focus on the Legacies of the war and the Fall of Singapore (zone 2). The first gallery, titled War, introduces you to the planning involved leading up to the invasion of Singapore on February 1942. As well as the battles fought by the local army regiments to hold against the Japanese forces, which, under the command of notorious Imperial Japanese Army general Tomoyuki Yamashita, an led the invasion of Malaya and Singapore, conquering both countries in 70 days despite being outnumbered in forces.

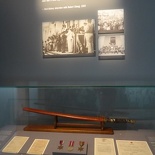

A number of military items, such as water canteens, POL equipment and weapons are on display here too. Artifacts of interest here will be the Map of planned invasion of Singapore island used by the Japanese themselves, showing the various points of entry across the Straits of Johor where the Japanese crossed over and broke through Britain’s “impregnable fortress” taking over the entire island in 7 days. This gallery is dark and gloomy, with all exhibits laid behind sealed behind glass cabinets.

The Surrender room

The Ford factory is also where the British forces surrendered unconditionally to the imperial Japanese army on 1st February 1942; this turning point in the war granted the factory its key installation status as a protected site crucial of Singapore’s history. The following gallery houses a mock-up of the room and table of the infamous scene, the scene immortalized from dated photographs of the event. The next third zone talks about the life in Singapore after the Japanese took over (becoming Synonan). This includes the “cleansing” of groups deemed to be a threat to the Japanese agenda and how certain able-bodied ethnic groups were deliberately executed just as they were sensed to be a threat on baseness grounds, a solemn zone indeed.

Life during the war

Under the Synonan rule saw a life of constant fear where everybody had to submit to the way of the Japanese. This saw radical changes to way of life, such as forced learning the Japanese language in schools, being always under surveillance and the introduction of banana money. There were constant policing to ensure that everyone is loyal to the Japanese- anybody who were reported working against the Japanese could be deported and executed.

Interestingly, through the displays, you get provocative questions printed at the bottom of the displays, invoking you to think about what you would do in that situation, like “if you have a close family member who you know is working against the Japanese, will you report him to save your family?”, a nice creative touch.

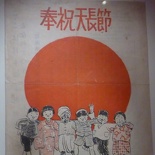

The life of a prisoner of war (POW) was also shared through written and picture diaries; the walls of the POW zone are lined with sketches and drawings done by the inmates, documenting their time as prisoner of wars. It speaks of life in overcrowded prisons and the eventual fall and withdrawal of the Japanese from Singapore following the American bombing of Nagasaki and Hiroshima. On display too was propaganda materials such as magazines with literature and photos showing false information back to Japan that the people and children in the newfound territories benefiting from education and socializing under their new found rulers. The photos sent back to Japan were staged, completely hiding the bloodshed of war to the people in Japan itself.

End of the second world war

The final zone 4 of the wartime exhibits covers the Legacies of war and occupations. This includes honoring the Singapore wartime heroes, such as Chinese resistance fighter Lim Bo Seng. The exhibits then transitions onto a timeline summary, with key incidents printed on the walls. Information here focused on the combined international efforts, including the Allied push from 1942 which eventually led to the end of World War Two. This sector is themed to that of jungle warfare, with army camouflaged netting laid suspended over the walkways. This zone ends with a small room with quotes of the war. This closes the first part of the main gallery exhibition, focused mainly of the Japanese occupation. The gallery then exits back out into the Museum lobby, and continues to the era after the war via a separate sliding glass door entrance on the opposite end of the lobby.

Post-war era

This last gallery has a more uplifting ambience, clad in neutral grey, the exhibits here comprise of a mix of information on walls, static displays and audio-visual screens. It is also much smaller, with all the exhibits placed in a single large room compartmentalized by glass walls. Following the surrender of the Japanese, in the midst of the joyful Japanese surrender ceremonies which ran after the war, came the daunting task rebuilding Singapore and picking up the pieces thereafter. This also marked the return of the “Fair weather” British who had to face the daunting task to make up for lost trust in the Singapore people, having not only lost the Singapore battle to the Japanese, but abandoned the island when the Japanese invaded, given priorities to reinforce their forces to support the war back in Britain against the Germans.

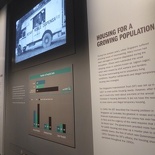

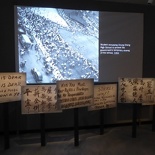

Many of the remaining Japanese were tried for their War crime trials in Singapore, delivered through a collection of historical oral interviews. Next came the focus of addressing society needs from 1947, such as housing for a rapidly growing post-war population as trade and immigration returned back to Singapore. People were not happy with how some of the reform measures were run, which led to events such as the Chung Cheng High school protests.

In understanding society needs through social survey results, the country faced shocking levels of overcrowding as, giving birth to the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT) which eventually laid the founding of the Housing Development board in Singapore we see until today.

Other notable implementations following the war is the introduction of the Rendel Constitutional commission, appointed on October 1953 which set forward the changes to the Singapore constitution, including inclusion of the post of Chief Minister and minister appointees. This set forward the groundwork for the birth of the modern Singapore Parliament.

The gallery ends in a room playing archived audio interviews of the survivors of the Japanese occupation, describing of the hardship and suffering through the voices of the people who experienced it- you can sense the anguish and sorrow in their voices, speaking of a War which no one should deserve to experience. By this room is a display and recollection the current 6 war memorials in Singapore all laid in a map showing their points of interest, such as the Kranji war memorial, Indian national army, cenotaph at the Padang, Japanese Cemetery Park. This gallery exits back out into the museum main lobby again.

You are good to visit both pre and post war galleries in under 2 hours. The museum is not large and is kept up to date with regular expansion and upgrading of exhibits with items rotated out of the National Archives.

The National archives of Singapore

Speaking of the National archives, I will take the opportunity to talk about the National Archives of Singapore (NAS) building, which is this modern looking structure on the left of the museum compound. The NAS is the custodian who does archival of materials of national and historical significance. Their main building is one off fort canning, with the one here being a secondary site. These materials that NAS collect and preserves print material, including papers, documents, photographs, maps and posters up to the 19th century from government, private organisation and individuals. AV content includes videos and sound recordings.

These exhibits are on display in museums affiliated by the National heritage board all over Singapore, and are regularly rotated and when not on display are stored here in temperature controlled environments to prevent degradation. The National Archives building is not publicly accessible.

Gallery name controversy

The gallery’s initial “Synonan gallery” name on opening had been a topic of controversy among Singaporeans, which prompted an outcry on the media about the name suggestively glorifying the Japanese Occupation. Following a decision to quench to outcry, even requiring the intervention of the Singapore Minsters, the gallery was subsequently renamed from “Synonan gallery” to “Surviving the Japanese Occupation: War and its Legacies”, with all the museum print, signage’s and promotional material all revamped to reflect the new name.

That’s quite a mouthful. I am not assuming that the museum’s intended visitors are so shallow that you need literally the entire synopsis of the museum to be included into the venue name, just to get people to understand what the museum is all about. This is definitely not a high moment in the museum’s history for sure. Now I can totally see people going: “Hey! we have a free afternoon, let’s go to the Surviving the Japanese Occupation: War and its Legacies, to learn more about the Japanese Occupation: The War and its Legacies!”

The “Surviving the Japanese Occupation: War and its Legacies” museum staff also voiced their discontent in welcoming visitors to the “Surviving the Japanese Occupation: War and its Legacies” now with a mouthful barrage of words and spurting saliva.

I can share the museum’s staff sentiments into preferring the older, catchier “Synonan gallery” name. The new name is too unpractical, long-winded and probably not well-thought through just to please an angry mob. The point is that War and history are all already cast in stone in the history books, and no-extent name-changing won’t mask the reality of the atrocities of the Second World War in Singapore. Furthermore, “Synonan” is a name unique to Singapore during the Japanese occupation, which I found is more fitting to the gallery’s regional displays and main focus- primarily focused and set upon Singapore’s dark war past.

The name of the venue is not only one sought with controversy but ambiguity too, the museum staff also shared some humorous experiences they had with delegates from the Ford Motor company stepping into the museum and asking “where the cars” are, only to realize that the museum is not the automotive museum there were expecting.

The museum is open daily 364 days a year (with exception of the first day of Chinese new year) 7 days a week from 9am to 5: 30pm. Entry is free for Singaporeans, where an entrance fee of $3 is applicable otherwise.

Surviving the Japanese Occupation: War and its Legacies (Synonan gallery)

351 Upper Bukit Timah Road

Singapore 588192

[…] are open 9.30am to 6pm daily and closed on Mondays. Entry is free to Singaporeans and like the Old Ford factory museum and the Discovery center at SAFTI we visited on our previous museum […]

[…] expand your history knowledge includes the Synonan Gallery. Also, it is as part of the memories of Old Ford Factory exhibitions, complimented by the Reflections of Bukit Chandu museum too. Similarly covering the Japanese […]